"How Long, O Lord?' - second part of chapter 2 (fragments) from "In the silence of Mary- the life of Mother Mary of Jesus Carmelite Prioress and Foundress 1851-1942"

"How Long, O Lord?' - second part of chapter 2 (fragments) from "In the silence of Mary- the life of Mother Mary of Jesus Carmelite Prioress and Foundress 1851-1942"

In this chapter we read about Madeleine adolescence and her difficult task to inform herfamily that she will follow the will of God in her life and enter the cloistered life.

It was at this church (Jesuit Church in Paris) that the girl found the confessor who was to be more help to her than anyone else, even than M.Dambre. Pere Ambroise Matignon became her firm friend, followed her up even after her entrance to Carmel, and made the journey to London several times to help English Foundation in early days. She need not tell him about her vocation, for he saw it as plainly as others had done, and it may have been under his direction that she first ventured to speak to her mother, at the age of eighteen. One might have hoped that a blow so long expected would have fallen in consequence more lightly, but it was not so. Mme Dupont's grief was heart-rending, and a terrible suffering to her poor daughter. Detachment is not indifference, and the love of God makes a heart more, rather than less sensitive. The memory of her own suffering would be revived often during her long religious life, and all its anguish relived in the trials of her children. She told them then what she was learning now, that one can only trust those one loves to God, for Whose sake it is that one has to break their hearts. 'When we surrender unreservedly to Him, we trust to Him all those we leave for His sake. Then, with all love, He accepts the responsibility; he watches over them Himself far better than our filial tenderness could ever have done'. It would have been something if the end had been in sight, but the stricken mother forbade her to mention the question to her father before she was twenty-one, or even to refer to it again to herself. For her own sake as well as Madeleine's she would have been better advised to have yielded at once. The next three years, during which she clung so desperately to her daughter, were a period of what the latter described as 'reciprocal agony', in which each of them unwillingly became a source of pain to the other. Madeleine accepted her mother's decision as God's will, though she warned her that time could make no difference, since her resolution was irrevocably taken....She strove to be gay and cheerful; if sometimes the nostalgie de Dieu looked out of the grey eyes, who shall blame her? Amongst the family and friends, it had been long suspected that she was only waiting for the day when she would be free to enter Religion...

By the end of 1869, there were, of course, other subjects to occupy the minds of a good Catholic family. The Vatican Council, with all the controversy that raged round it, became the vital topic of conversation. Madeleine had a tremendous devotion to Pio Nono, which lasted all her life. In her old age she loved to recall for the younger generation the dramatic climax of the Council, when the aged Pope solemnly promulgated the dogma of Papal infallibility, with the lightning flashing round his head. 'It was magnificent' she used to say, her face aglow with enthusiasm; 'you feel that God is there'. The fearlessness and determination with which the decree was made in the face of fierce opposition made an appeal to her own unflinching loyalty to God's will. Did she hear the name of the Englich Archbishop who became one of the best known of all the Fathers of the Council? It is very probable, for Mgr Manning traveled to Rome with Mgr Mermillod, the Dupont's old friend. All through the anxious summer days of the Council, ...a storm of another kind was brewing over France, and on Tuesday, 19 July, the day after the Coulcil had solemnly ratified the Papal Decree, war had been declared and the first offensive taken....In January capitol surrendered, only to fall almost immediately under the worst affliction of the Commune.....Mr Dupont who remained in Paris was recognized one day by Communists at station entrance as a notorious Catholic and (mob) clamoured for his arrest.....Mgr Darboy, the archbishop, and many of his priests. including some Jesuit friends, had been shot in cold blood. Pere Matignon (Madeleine's confessor) had only escaped by a hair's breadth.

It was during this, her twentieth year, that Madeleine one day entered the chapel of the Carmel in the Rue d'Enfer for the first time. ..... The first impression of any Carmelite Monastery is rarely prepossessing; the high, forbidding walls, the bare, austere chapel with its formidable looking spiked grating do not offer any merely sentimental attraction to the Religious life, nor do they betray the joy of those who dwell within. Madeleine shuddered at the place, with its dingy environment, and noticed that it had a noisy barracks for nearest neighbour. What a contrast to Lavaur....Yet as she knelt in the chapel, it was said to her, in an interior and spiritual manner, that here and not at Lavaur, she would find true life, and would consecrate herself to God. At the same time, though less distinctly, she understood that her future

work for Him would lie in England. She did not mention this intimation, even to Pere Matignon, since she never shaped her course by such things, but rather waited for events to prove their truth. Finally her twenty-first birthday came, and she faced the agonizing task of begging her father's consent to her departure. Of that interview she never spoke....Her father's sorrow was, indeed, immense, but he was too good a Catholic and too upright to refuse or stand in the way of her conscience; he gave her the permission she sought, though she knew what it cost him. Still she waited for some manifestation of God's will as to the place of His choice, hoping against hope that her intimation might have been wrong, and that Lavaure might still be her home. At the last moment, however, Pere Matignon refused to allow her to enter there , and told her to pray for eight days before deciding upon a Paris Carmel. The decision left her without regret, despite the natural sacrifice, for it was God she wanted, not a particular community. She carried out her confessor's injunctions, and again in her prayer, this time in the Church of Notre Dame des Victoires, the Carmel of the Rue d'Enfer was shown to her as God's choice. Pere Matignon himself effected the necessary introduction; his recommendation of her was succint and expressive: 'C'est une perle'. Arrangements were quickly concluded, and the date of her entry fixed for Low Sunday. On that day, 7 April 1872, after a last night of tears with her grief-stricken mother, and well-nigh exhausted by the protracted suffering of the separation, she crossed the treshold of Carmel, and the enclosure door shut behind her.

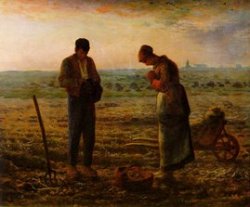

The second picture shows Madeleine and her mother, just before she entered Carmel.